Today, N.W. 23rd Street—better known now as the Uptown District—is a youthful hipster’s consumer paradise of chi-chi escape rooms, Phish-themed vegan eateries and moderately upscale marijuana dispensaries.

A little over two decades ago, however, it was a McCormick bottle-strewn no man’s land that housed run-down bodegas, multiple wig shops and, of course, the Centeon Plasma Donation Center, the one true business that kept the area thriving; twice-weekly visits there kept me rolling in canned Stagg Chili, six-packs of Diet Doc Shasta and the occasional handful of GPC looseys during those ultimately useless college years.

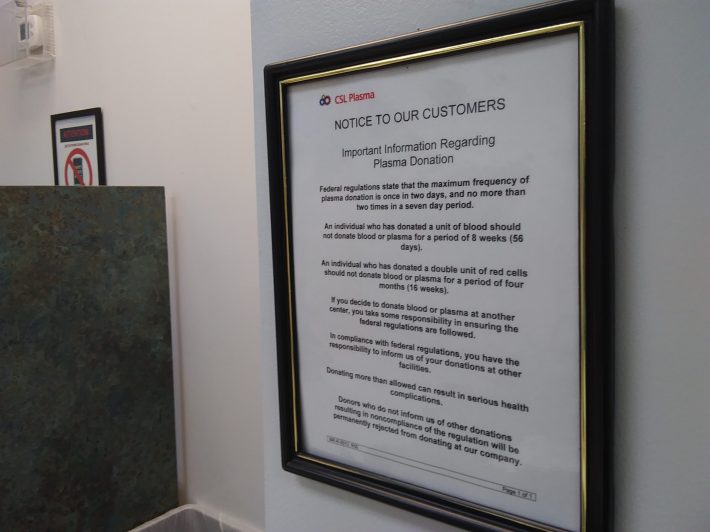

Earning roughly $25 a donation, the 90s were a time where, as long as you hadn’t been to Haiti in the past six months or had sexual relations with someone who had been to Haiti in the past six months, you were allowed to donate up to two—sometimes three, if no one’s looking—times a week. I took full advantage of it, for as long as I humanly could.

After a short examination to make sure there were no fresh track-marks on your arms or between your fingers, you were then led to the donation lounge. As the bitter scent of bleach lingered in the air, you were strapped to a table and given a ball to squeeze; as the crimson blood shot out of you, the machine next to your head made a strange whirring noise. When it stopped, a cool clear solution was inserted back into your body, a chilling sensation that reverberated throughout for the rest of the day.

Do this for about an hour—and, whatever you do, don’t fall asleep—and you’ll probably be walking out with a couple of bucks soon enough; I’d cash the check at the convenience store up the street, purchase a medium cola from Church’s and then wait out front for the 5:15 bus to come rolling right along.

While this practice mostly stopped when I left OCU to become an employee at a bustling local movie-house or two, a few friends and family have continued to still donate plasma throughout the years, the generous giving of it being a second career for a few of them. As a matter of fact, a close relative has financed his son’s entire Christmas for a few years now through a month’s worth of these plasmatic scrapings.

Recently, a lovely friend and I had gone to coffee at the upscale bakery Cuppies and Joe, located across from the now-named CSL Plasma on N.W. 23rd. Sitting there, sipping my dank drink, I saw the same people—thin, weak and impoverished—that I did twenty years ago go in and out of the building, some piling into a car, a few loading their goods on a bike and others just backpacking on to their next spot.

I wondered how plasma donation in Oklahoma City had changed in these past couple of decades and, even more so, would I even be eligible to donate anymore; like most people, an extra $25 in my pocket could always come in handy, even if it was through selling my much-needed plasma to burn victims, cancer patients and others with a license to be ill.

In case you need a quick refresher, plasma—often referred to as the “gift of life”—is the essential starting material needed to manufacture therapies that can help with healing rare, chronic diseases; once cleared for donation, your blood is drawn and the plasma is separated from it by machine. Then, through a process known as plasmapheresis, your red blood cells are returned to your body. Repeat as needed.

I walked into CSL that afternoon, ready to go; my blood pressure was low and my plasma was crying to be released from its blood-borne prison. After I showed the white-coated receptionist my driver’s license and, oddly enough, my social security card, I was led into a small white room with two other people to do a vein check.

A scent reminiscent of nail-polish remover was very strong in the surrounding air, but the place did look far cleaner than I remembered, with scrubbed white tile and walls that were decorated with the most festive of dollar store demons and ghouls for Halloween.

I stretched my arms out and a lab tech tapped my inner-elbow; while many doctors in the past have told me that I have shallow veins, here, the tech gave me a “code yellow” and I was allowed to proceed for a check-up. The couple next to me, however, were both given “code reds” and asked to leave.

The rates for donation have practically doubled since my last donation here, with the first five donations now coming in fast at $50 each—that’s even better than minimum wage, I told myself as a man in camouflage pants nodded off next to me. Over his shoulder stood a statue of la Llorona, the famed Mexican crying woman, her glowing eyes piercing deep into my already unnerved soul.

The doctor called my name and, I gotta tell you, he was probably the coolest doctor I’ve ever met and, as you know, I’ve met quite a few; with tousled hair like a stoned skater and a vernacular like that of a stoned surfer, this Spicoli-esque medicine man told me that, because I am over the age of 40 and have had a hemorrhagic stroke that I was unable to donate at their clinic.

Thankfully, he punctuated it with “Sorry, dude!” which really seemed to lessen the blow.

As I walked out of there without so much as a parting gift such as a t-shirt or a tote-bag, I took a snapshot of the signage outside; a homeless man securing his bike yelled at me to delete the photo or he would “kick my ass,” his worn clothes, random electronics and other trash spilled out from his knapsack, blowing down the concrete in the warm wind. Now that was the 23rd Street that I remembered.

_

Follow Louis on Twitter at @LouisFowler and Instagram at @louisfowler78.