In the Summer of 1999, I had just been ghosted by my girlfriend. As soon as we both headed home from OSU, she just stopped returning my calls. With my plans of Summer romance curtailed, I channeled the hurt and confusion into exercise, pledging to return to Stillwater yolked up in a way that would make her question why she’d given up on me. Or something, it wasn’t a well-crafted plan.

It was with that goal in mind that I got in my car that late July afternoon and while driving down my parents' street toward my gym, I saw a team of officers carrying the largest guns I’ve ever seen outside of a movie. The sight of a Red Ryder bb gun is enough to make me feel physically ill, so I did not do the looky-loo thing that many in my position would try. Instead, I continued my path to the Northside Y and tried to put it out of my mind.

About an hour later I was taking a break between sets to casually watch the Wheel of Fortune episode being shown on one of the televisions in the cardio area. Just as someone was about to solve the puzzle, the local news broke into programming, something that usually only happens if a tornado is on the way. Instead, it was an announcement that the OKC Police had issued a request for information on the whereabouts of Julius Darius Jones.

This caught me by surprise. Until then, I’d never known my classmate's middle name.

–

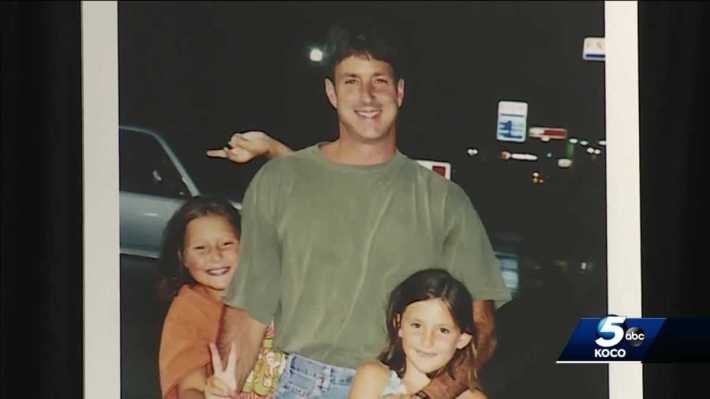

Paul Howell’s murder was a tragedy.

Regardless of how one feels about the aftermath, all should be able to agree that he is the true victim of this story. The insurance executive had just taken his children back-to-school shopping and had pulled into the driveway of his parents’ Edmond home when he was approached by a young black man covering his face with a red bandana. He had a gun that was used to murder Howell in front of his children. The attacker(s) drove off in Howell’s Chevrolet Suburban.

This story was catnip for the Oklahoma media. It splashed the front page of The Oklahoman and led every newscast. The salacious details that included the horrible PTSD inflicted on the two young girls were just what news producers needed during a time of year where OU football was in hiatus. Nestled in every story was the suburban horror story of black youth invading a white neighborhood.

Needless to say, the consumers of that media needed a satisfying conclusion to this story.

–

At John Marshall High School, I had one class with Julius Jones. It was the first accounting class I ever took, a subject that just instantly made absolute sense to me. Julius, who was a couple of years younger than me, and probably didn’t belong there. Debits and credits escaped him, as they would most high school freshmen.

I had known Julius’ brother through baseball, so I felt a kind of duty to help the little brother. As he struggled through the assignments, I attempted to teach him the concepts in a way that he could hopefully grasp. It didn’t take. He transferred out of the class a few weeks later.

During that month or so, I interacted a lot with Julius. He was clearly a smart kid, kind of quiet like me. But unlike me, he had an air of confidence. Some of that probably came from the popularity he built by being the starting quarterback for his middle school football team, though arriving at that position very well could have been related to that confidence he already exuded. Either way, he knew he was cool. My most vivid memory of interacting with Julius was when this freshman preached to me the importance of “crisp creases” in your jeans. It was important to his look. His look was important to his image. His image was important to him.

That thought occurred to me a lot as his story unfolded.

–

Capital punishment is a topic that I have considered a lot over the years.

During the point in my life where Julius Jones was accused, and later convicted, of Paul Howell’s murder, I was very strong proponent. It was a position I could point at to illustrate my moderate leanings around the conservative man-boys that surrounded me at OSU and wrote off my opinions as the handwringing of a bleeding heart.

The justice of an eye-for-an-eye appealed to that immature version of me. I told myself that the people on death row were incurable monsters whose actions had made their life forfeit. I told myself that their presence in our prisons wasted resources and clogged up beds needed for criminals who could be rehabilitated. I told myself that the criminal justice system had plenty of opportunities to nip their path to death row if they were innocent.

In other news, I used to be young and dumb.

–

Julius Jones was just given an execution date of Nov 18th despite the Pardon & Parole Board recommending his sentence be commuted. Help us SAVE HIS LIFE by contacting @GovStitt at https://t.co/OR1WGMlPDI & asking him to commute Julius’ sentence.#JusticeforJulius @justice4julius pic.twitter.com/bj62ZChj3z

— Kim Kardashian (@KimKardashian) September 20, 2021

I’m not sure how Kim Kardashian got involved with Julius Jones’ quest for freedom. I do know that the Jones family always had a goal of making Julius’ plight a big deal. “We’re going to get Johnnie Cochran,” was a rallying cry that, apocryphal or not, was attributed to Mrs. Jones in the John Marshall alumni gossip channels.

Cochran, known for clinching O.J. Simpson’s acquittal with the epic “if the glove don’t fit, you must acquit” tagline, died soon after Julius’ arrest and was never going to work in Oklahoma. Instead, the Joneses were stuck with just a normal lawyer that used a normal strategy and the results were a capital murder conviction.

The family clearly never gave up. By the time Julius had run out of appeals, his case was a cause celebre among the media elite. There was Kardashian with her former husband (some guy named “Kanye”) lobbying the highest reaches of the government and bringing the story to her tens of millions of social media fans.

Russell Westbrook, Baker Mayfield, Trae Young, and Blake Griffin (whose father coached Julius in basketball) also took up the cause. Viola Davis produced a documentary series, The Last Defense, that was picked up by ABC. The number of celebrities that have been at least peripherally involved in bringing attention to Jones’ situation is likely in the dozens.

Without that, he was bound to die in obscurity. In the end, it may be the final reason he ends up dead.

–

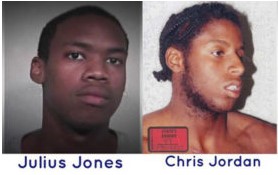

Chris Jordan is someone I have never met. He transferred to John Marshall after I graduated to help reload a basketball team that had just lost three D-1 players. On that basketball team, he became acquainted with Julius and built a friendship that likely culminated in the Howell murder.

The mutual acquaintances I share with Jordan have a common adjective for describing him. The word “idiot” is always one of the first things said about him. For instance, there is the guy who played with Jordan at Edmond Santa Fe that says the white guys on that team, whose only knowledge of gang culture came from listening to 2Pac’s “All Eyez on Me,” dubbed him “Westside” because Jordan pretended to be gangsta. Another friend who knew Jordan from pick-up basketball described the way Jordan always talked trash on the court in a way that suggested he was hoping to start a fight. Others tell me he was constantly in trouble in class.

When Julius went on trial, it was Chris Jordan’s testimony that convinced an almost exclusively white jury to pass the sentence against Jones. Prior to becoming the star witness, he was Julius’ co-defendant. If you believe the story lined out in The Last Defense, Jordan is a criminal mastermind.

–

While not quite the boogeyman that suburbanites believe it to be, gangs are a real issue inside the city.

When I attended John Marshall, most of our rivals called us “Slob” Marshall – the “slob” being a slur toward members of the Bloods gang by other gangs. Our school colors were red (the color representing Bloods) and blue (favored by the rival Crips), so when athletes would wear jerseys that were primarily blue, a lot of them would put band-aids on them. Thanks to my privilege, I just thought this was a fashion trend, so I’d put bandaids on my clothes. Turns out, that was meant to represent that just because they were wearing blue it didn’t mean they were Crips.

In my years going through Oklahoma City schools, I was surrounded by gang activity, but my status as a straight-laced white kid mostly shielded me from what was happening. There was the time one of the baseball team’s best pitchers had to quit the team to focus on “slangin’” and another baseball teammate who thought it was funny to teach me hand symbols that would get me “capped.” Generally, though, it was a different universe that I somehow existed inside of.

That was not the case for most of my black male schoolmates. There was constant pressure to affiliate. Those that did not were often ostracized.

Other than the theatrical part of being in a gang, the cosplaying of the media that was popular in the nineties, I never understood the draw. Getting in involved hazing. Being in limited your social circle. Their ideas of entertainment seemed foreign.

Then, going to college and joining a fraternity enlightened me. Those same criticisms I had of gangs were the same things lobbed at me by the anti-frat independents I would encounter. In the house, we used a lot of the same terminology, like calling fellow members brothers. While the crime we organized was more socially acceptable (i.e. underage drinking), a big part of our identity was providing that illicit service.

The fraternal bond was intoxicating. There were plenty of guys who without the commonality of three Greek letters, I never would have spoken to, yet for our years in Stillwater we were brothers. We would feud with other guys simply because they had different Greek letters on their shirts, the way Bloods and Crips would. And, also very similarly, one of the draws of joining a Greek house was the promise that the affiliation would lead to financial reward.

All of those benefits likely help explain why Julius Jones wound up a Piru Blood.

–

If you believe the narrative pushed in The Last Defense, Julius’ first involvement in the Paul Howell murder happened the day after.

On that day, Julius slipped out of his parent’s house without telling anyone and just happened to run into Chris Jordan who was driving through the neighborhood at that very moment. Jordan offered him a job driving a stolen Suburban to a chop shop run by a police informant on the Southside of OKC.

Unknown to Jones, this was the vehicle that was at the center of the story that was headlining on news stations throughout the area. He says he agreed to this, in the kind of small confession one makes to sound more reliable when making bigger denials, because he had a “desire for finer things.” This, he insists, is why his fingerprints were found inside the vehicle when police located it abandoned at a convenience store near the chop shop.

After failing to pawn off the vehicle because it was “too hot,” Jones and Jordan went back to Julius’ parents’ home. This is the time when Julius suspects Jordan hid the murder weapon in the Jones’ attic. That’s where the police I saw running the fence line found it a couple of days later.

Jordan, who was the co-defendant until he accepted a plea bargain that forced him to spend 15 years in prison, had a different story that he told the jury. The trial transcript isn’t readily available, but rest assured, in that one Jones acted alone.

Neither man should be considered a reliable narrator. One thing that Jordan failed to address in his narrative is why the eyewitness accounts of the murder seemed to describe his appearance when they talked about the shooter. A major point of contention by those trying to free Julius was that the witnesses mentioned that there was hair sticking out from behind the stocking cap worn by the murderer.

If there is one feature that was always true about Julius Jones, it was that he had short hair. It was part of his image, the same image so important to him that he admitted doing crime to maintain it. Julius never grew the hair out, and it was always well groomed.

The day both men were captured by police, they looked like this:

In The Last Defense, Jones alleges that the police zeroed in on him and failed to consider any evidence to the contrary. He also claims that the officers who arrested him peppered him with racial slurs, something he feels contributed to their disinterest in finding the real killers. Then, the trial was a farce where a disinterested public defender allowed the jury to be stacked against him while failing to poke holes in the testimony of the guy he alleges actually killed Paul Howell.

After a lifetime of consuming true crime stories and a year seeing nationwide protests about police forces being packed with white nationalists, it only sounds kind of crazy.

More recent evidence comes from jailhouse confessions supposedly uttered by Jordan when he was serving time in Arkansas. At least three fellow inmates have reported that Jordan admitted the crime to them. One of the reports came from someone who wrote:

“I can even recall him making statements such as ‘I’ll fuck you up like I did that man,’ this occurred when would be on the basketball court and things would get heated.”

That’s exactly the behavior described to me by people who have played against him. While convicted felons make for unreliable witnesses, this was not a secret supposedly confessed in private. And while the State was clear that these snitches were of a class that should be ignored when it came to sowing doubt, they were very certain that the convict who was originally Julius Jones’ co-defendant was a solid source for conviction.

–

The Pardon and Parole Board were swayed.

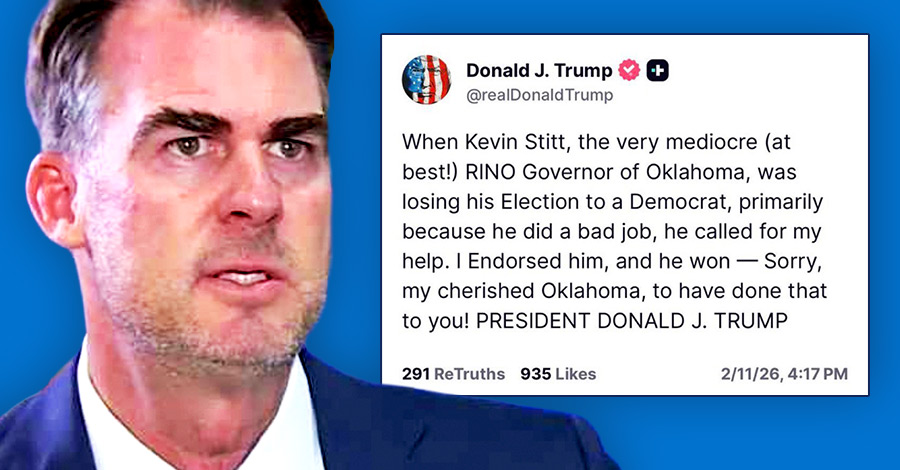

The board, built with appointments by Governor Kevin Stitt, voted 3-1 in favor of commuting Jones’ death sentence to life in prison. Reasons for voting in favor of commutation ranged from the scientific (Kelly Doyle pointed to research on the still-developing brains of 19-year-olds) to the procedural, but all three voters in favor expressed “doubts.” The lone holdout, Richard Smotherman, preached his concerns about setting a “precedent.”

Merely a recommendation, the Board’s commutation suggestion now goes to the Governor of Oklahoma for the final verdict. The timeline for Stitt’s decision was moved up significantly when the Department of Corrections set November 18th of this year as Jones’ execution date.

–

David Prater is big mad.

In a speech that kicked off with a diatribe against “George Soros,” “liberal elites,” and “Hollywood,” the Oklahoma County District Attorney whined about how the Board allowed a clemency advocate to speak on behalf of clemency. Most importantly, he voiced shame at this state for not following through on its commitment to put men in body bags.

The Trump-y preface was no mistake. This press conference was a direct appeal to Governor Kevin Stitt to overrule the Board that he put in place. As far as theatrics, it is a smart ploy. Because if there are three things Stitt’s base won’t want him associated with, they are George Soros, liberal elites, and Hollywood. While smart politics, the performance barely hid the agitation of a serial killer being denied a victim.

–

Those who want to execute Julius Jones plead that it will bring “justice” to the family of Paul Howell.

Noted Lost Ogle superfan Barbara Hoberock interviewed Howell’s daughter for an article that emphasized the family’s firm belief that Jones was the person who committed the murder, and the hurt being caused by celebrities supporting his story. Justice, though, was not something Hoberock asked about.

I would have been interested to read what the daughter of the victim thought about the State of Oklahoma enacting the same pain she feels on the family of Julius Jones. Her belief in the guilt of Jones may be firm, but his family is just as convinced of his innocence. They have spent the past twenty years believing their son/brother is on the verge of a state-sanctioned murder.

Even if Hoberock had asked, the answer was likely to play out like the scene in The West Wing’s episode “Take This Sabbath Day.” In the episode, the President was tasked with deciding whether to commute the sentence of a man scheduled for execution. Soliciting advice, he asked his personal assistant, whose mother was a police officer who died in the line of duty, whether he would want his mother’s killer executed. “No,” the man said, “I would want to kill him myself.”

Vengeance is the purpose of capital punishment. As far as justice, though, it is flawed from the premise.

In the judicial system, execution is only supposed to be meted out for murder, and then, only to the most heinous of killers. First-degree murder requires malice and forethought.

Yet, what killing has more forethought or malice than an execution? The District Attorney asks twelve jurors to pass the sentence. A judge accepts their verdict. Appeals drag the process for decades. When those run out, the Department of Corrections schedules the killing. Then, they must find a physician who will ignore the first line of the Hippocratic Oath and procure the weapon from a pharmacy. In the end, human life is extinguished.

In saying that premeditated murder is wrong, the government carries out the ultimate act of premeditated murder.

–

When the Pardon and Parole Board voted to recommend commutation, the only message that sent was that execution was not the proper remedy in this case. With his appeals exhausted, Julius Jones is never going to be deemed innocent by the State of Oklahoma.

David Prater’s pride may be wounded from the suggestion of malfeasance, but his office’s conviction stands. The Howell family may be disappointed if vengeance remains the Lord’s. When all is said and done, though, their justice is served.

The only question that remains is whether the State of Oklahoma will carry out the state-sanctioned murder of Julius Jones. Governor Stitt is on the clock.

–

As a writer, I live inside my head.

My youngest is learning narrative writing in school right now, and frustrated, he told me he wishes he could just write down the things he has in his head. I have the opposite problem. Everything I think gets written in my mind, being edited over and again until I finally put it down on a page.

This story has been rattling around, robbing me of sleep for many years. It started as a twinkle of an idea in the early days of the Ogle, "hey I should write about the guy I know on death row!" That was, what, thirteen years ago? The story has metastasized or faded many times. But as the reality of the ultimate fate gets closer, I hope that getting it onto the screen will bring some semblance of relief.

Some of these thoughts gut me. For instance, what if I had been able to better explain the difference in debits in credits in how they relate to asset or liability accounts versus income statement accounts? Would Julius have stuck out Accounting I? Maybe we would have gotten to know each other better and I could have encouraged him to follow my path. Perhaps he could have folded into my peer group instead of befriending guys like "Westside" Jordan?

Part of me prays that he was a lost cause and that nothing I failed to do would have made a difference. That same line of thought sometimes hopes that he actually did kill Paul Howell so that those who do believe execution is justified are getting the right person. For me though, it matters not. Julius, even if he truly is a monster, is a person. Murdering him will not resurrect Paul Howell. It won't bring satisfaction to the family of the slain, though it is certain to destroy a piece of many.

I would be one of those affected.

I hope they don't kill Julius.